I have spent the past four years staring at slide after slide of art: Jasper Johns, John Singleton Copley, Jan van Eyck … and the Johns go on. As an undergraduate at the University of Virginia, I was exposed to the cultural and social implications behind these artists and their work. I memorized myriad names and dates, and I made more flashcards than I care to count. My first-year art history class was held in a massive auditorium, and the floor to ceiling projection made each piece look more and more foreboding. Over the next three years, classes moved into smaller lecture halls, and I found myself seated at a crowded conference table, discussing the monumentality of Giotto’s use of internal modeling in the Arena Chapel. As my studies became more specific, I would occasionally find the time to visit with these works face to face in museums. I would tell anyone who would listen (so usually I was talking to myself) what I knew about the work in front of me, closing my eyes and reciting the dates aloud to see if I could remember them. It would often turn out that I could only remember half of what my teacher had so eloquently lectured, and my dates were at least five years off every time.

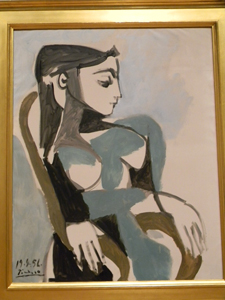

After graduating from U.Va in May, I returned home to Charleston to begin my summer internship with the Gibbes. I knew that I would be working with Zinnia Willits, Director of Collections Administration, and Sara Arnold, Curator of Collections, but I was not quite sure what “collections” entailed. My academic bubble of names, faces, and dates had left me completely oblivious to what goes on behind the scenes in the museum world. I understood that each work of art the traveling exhibitions at the U.Va Art Museum had come from somewhere else, but I never put any thought into who had organized the exhibit, or the hard work that was required to actually prepare and transport these works from one museum to the next. In my time with the Gibbes, I have touched (with gloves) etchings by James McNeill Whistler, drawn up a condition report on a William Merritt Chase painting, and witnessed the last minute conservation of a work by Picasso. The godlike artists of my college years have become more like aged celebrities – I still revere them, but I now know how much work has gone into keeping up their glossy façades, and just how many people it takes to get them from one venue to the next.

—Sarah West, summer intern, Curatorial and Collections Departments, Gibbes Museum of Art

Explore more of the Gibbes’ collection in our online database.

Download the Gibbes College Internship application (PDF).

Published July 20, 2010