We recently changed some of the works on display from the permanent collection and one of my favorite pieces is now on view: Anna Heyward Taylor’s Carolina Paroquet. Not only am I attracted to the Technicolor feathers of this fine bird, I’m moved by his sad story. The Carolina Paroquet (or parakeet) was first scientifically documented by Mark Catesby, an English naturalist who travelled to Colonial America in 1722 to document the flora and fauna of the wild countryside (stay tuned for an exhibition of Catesby’s watercolors opening at the Gibbes this summer). This beautiful bird was declared extinct in 1939, mostly due to loss of habitat. He was the only indigenous parrot to North America. Before that time he (and his less colorful female counterparts) ranged all over the Eastern United States from as far north as New York, as far west as Wisconsin, and all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.

Taylor’s Carolina Paroquet is currently paired with Ichiryusai Hiroshige’s Green Parrot on Crab Apple Branch. When looking at the two works side-by-side, it’s easy to see the Eastern influences on her composition and technique.

Artist Anna Heyward Taylor was also an amazing Carolina native. Born in Columbia, SC, in 1879, she travelled the world. She studied with William Merritt Chase in New York, became enthralled with Japanese prints while in England (and later in Japan), and even worked as a scientific illustrator on an expedition to British Guiana. All of these experiences coalesced to create something, I find, wholly captivating in her work.

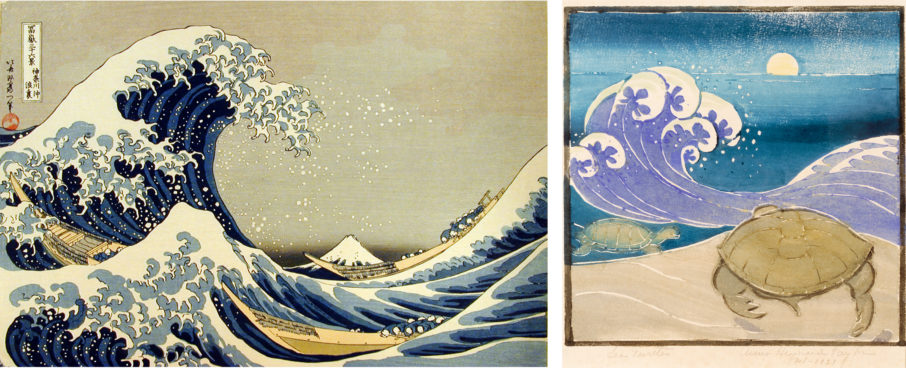

Another favorite work is Sea Turtle, also by Taylor (the green sea turtle is now an endangered species). Again, her obsession with Japanese prints is clear when considering Hokusai’s The Great Wave.

What makes this particular connection even more remarkable is that Anna Heyward Taylor donated this Japanese print to the Gibbes. We know that she was looking at that exact copy of The Great Wave when she designed her print. In a similar vein, I was inspired by her to create a unique stained glass window while I was still working as a stained glass artist at Blue Heron Glass.

As the Southeastern Wildlife Exposition starts today, let us all remember that part of SEWE’s mission is to promote wildlife and nature conservation. We should respect the world around us and consider our impact on the environment and the many different creatures who share it with us. While I’m thankful that Anna Heyward Taylor was able to capture the beauty of the Carolina Parakeet before it disappeared, it’s a shame that I can’t enjoy seeing him in my own back yard. (Although, my cats are better off since John J. Audubon noted the bird itself was toxic, from eating poisonous berries.) I’d hate to think of what other species might be lost to future generations.

—Becca Hiester, curatorial assistant, Gibbes Museum of Art

If you would like to see an actual specimen of the Carolina Paroquet, The Charleston Museum has a stuffed example on display in their Natural History hall. While it’s great to have an example now, this taxidermy practice probably did not help with the dwindling population.

Top image: Carolina Paroquet (detail), 1935, by Anna Heyward Taylor (American, 1879–1956); wood-block print on paper; 11 x 9 1/2 inches; Gift of Anna Heyward Taylor; 1937.003.0005

Published February 17, 2017