Naomi Edmondson, a former Gibbes intern and employee, recently received her master’s in art history and museum studies from Virginia Commonwealth University. A research project on digital mapping was inspired by Charleston Renaissance works in the permanent collection and she was excited to share this new perspective with her Gibbes family. She is currently living in Eastern NC and working as the Assistant Membership Chair for the North Carolina Museums Council. Naomi interned with the Gibbes Education Department from 2015-2016 and worked as a Visitor Services Assistant in 2016.

In May of 2016, I graduated from the College of Charleston with a double major in Art History and Studio Art. This May—in the very long year of 2020—I graduated from Virginia Commonwealth University with my master’s in Art History and Museum Studies. Besides the May graduation date that these two milestones have in common, they are also tied together by the Gibbes Museum.

I had decided I wanted to work with museums back in 2015, while interning in the Education Department at the Gibbes. Following my 2016 graduation, I worked as a Visitor Services Assistant after the Gibbes’ reopening, where I learned more about the collection. The romanticized images of “Historic Charleston” cultivated by the Charleston Renaissance artists in the collection resurfaced in my mind a few years later as I was finishing my graduate program. It seems only fitting that one of the last research projects completed during my Museum Studies graduate program should explore work in the Gibbes collection, where my passion for public history began.

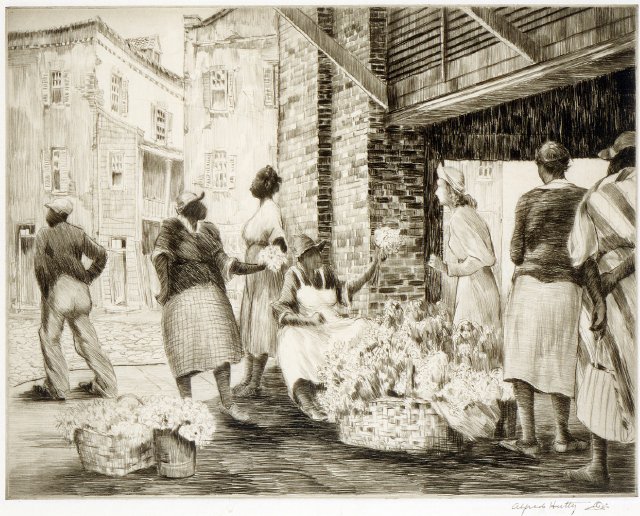

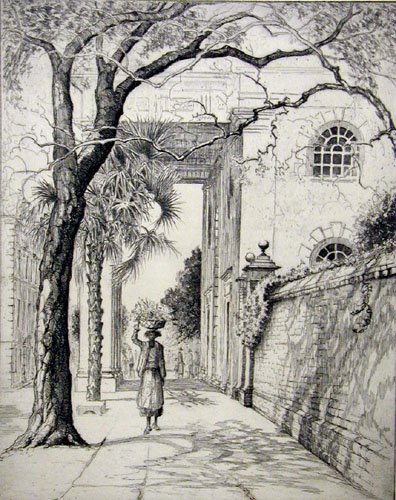

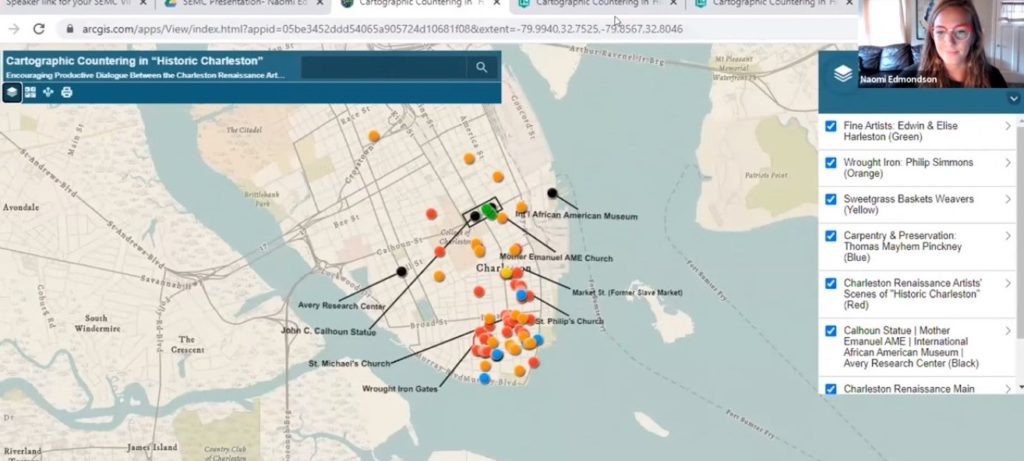

In a digital art history seminar, when tasked with creating a digital mapping project, I returned to a space I was familiar with: Charleston. Using this opportunity to hone in on the Charleston Renaissance artists in the Gibbes collection, I initially thought that by mapping out scenes from around downtown Charleston in these artists’ works (which are the red points plotted on the screenshot below from my project), I would shed further light on the ways in which this group of artists romanticized reality—specifically African American life—and perhaps create a useful tool for the Gibbes Museum, showcasing which areas of the city were of most interest to these artists and preservationists. (Of most interest were: St. Michael’s and St. Philip’s Church, wrought iron gates, historic homes, and African American vendors often shown with baskets on their heads.)

However, as I learned more about Edwin Harleston, the only documented African American “fine artist” who lived and worked in Charleston at the same time as this group—not referred to as a “Charleston Renaissance artist” but always mentioned as a counterpoint—I tacked on additional research questions… For instance, how did other African American contributions play into this image of “Historic Charleston” the Charleston Renaissance artists so wanted to project and what might those overlaps look like?

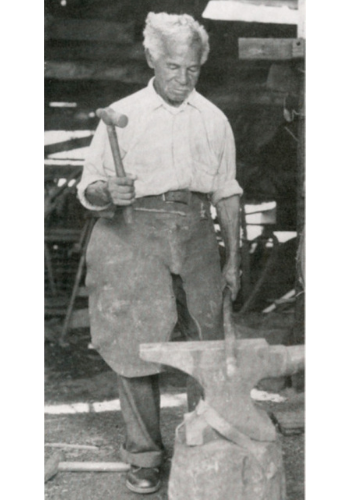

Without a doubt, the peninsula flaunted (and still does) the artistry of numerous African Americans within its own landscape and architectural makeup. For example, the ironwork of blacksmiths like Guy and Peter Simmons and later Philip Simmons, the carpentry and historic preservation of Thomas Mayhem Pinckney and others, and the sweetgrass basket weaving traditions of Gullah culture in street side markets both on and off of the peninsula. Recently, scholars have been interested in celebrating these histories of the building arts and so-called “folk arts” in Charleston, but I hadn’t found a project that put these contributions in direct dialogue with the overlapping interests of the Charleston Renaissance artists.

As a response, my project maps the interests of the Charleston Renaissance artists and then provides a “counter-counter narrative” to the Charleston Renaissance movement: African American artists’ and artisans’ contribution to “Historic Charleston” during the early twentieth century.

Visualizing these contributions to “Historic Charleston” on a map is a valuable way to use portions of the museum’s existing collections in a critical yet productive way, to create visual dialogue with African Americans artisans’ contributions to the city, using imagery from several other Charleston institutions (The Lowcountry Digital Library of the College of Charleston, The Philip Simmons Foundation, College of Charleston Special Collections, The Charleston Preservation Society, Historic Charleston Foundation).

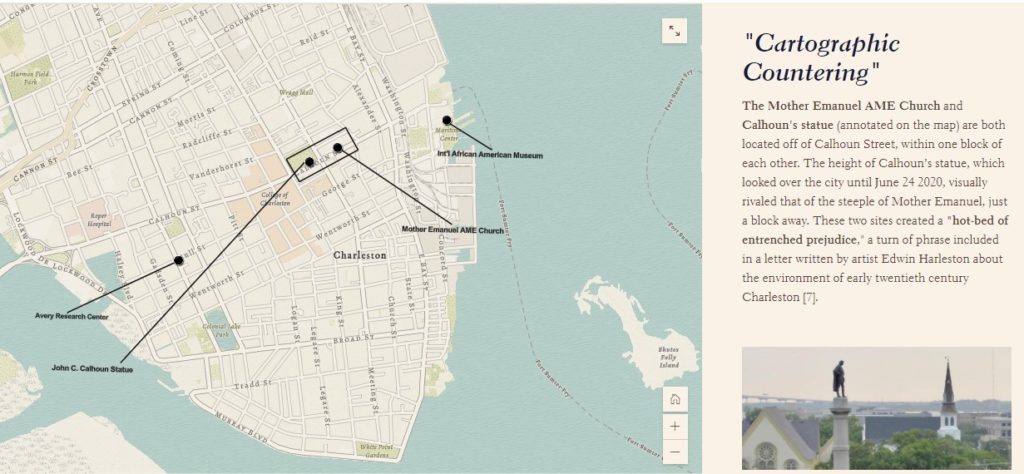

The idea of “cartographic countering” my map is built upon came about while considering the visual tension that existed between the John C. Calhoun statue which, until this June, rivaled the height of the Mother Emanuel AME Church steeple, just one block away. In the months following my virtual graduation, as cries for social justice and against problematic monuments rang out throughout the nation, the very landscape of Charleston shifted when Calhoun’s statue was removed from Marion Square. Because the city’s architectural makeup itself is a reminder of its fraught history, a map provides an innovative way to generate a counter-narrative for a scarcely documented generation of artisans and work that is difficult to display in the museum because it either hasn’t been preserved or is architectural in nature. My hope with this project was to allow early 20th African American artists and artisans to quite literally take up space in “Historic Charleston.”

– Naomi Simone Edmondson

Published October 30, 2020

Top Image: Flower Vendors at Charleston Market, 1948, by Alfred Hutty; dry point on paper; Gibbes Museum of Art.