This summer, I have been interning with the Curatorial and Collections departments as part of a long-standing partnership between the University of Virginia’s Institute for Public History and the Gibbes Museum. As a rising fourth year Art History major hoping to pursue a career in museums, I was excited by the opportunity to engage directly with a museum collection and the level of firsthand experience I’ve received at the Gibbes has certainly exceeded my expectations.

When I first came to the Gibbes, I knew, admittedly, little of the collection other than its vast holdings of miniature portraits and focus on artwork relating to the Charleston Lowcountry region. Whatever notions of regional South Carolina artwork I entered with have been completely debunked; through my time here, I’ve come to learn that these so called regional works tell a rich and pluralistic story of a place that transcends spatial boundaries to participate in a greater narrative of American art. Working at the Gibbes has stimulated my own academic inquiry into moments in art history that I otherwise would never have discovered.

To that point, one of the more memorable experiences I’ve had while at the Gibbes occurred while I was inventorying the museum’s collection of works on paper. I happened upon a drawer full of panels, each with a whimsical silhouette illustration accompanied by a caption describing the odd figures and events that transpired in the scenes. After looking at the records for the works, I found out that they were illustrations to a children’s book, though there was little other information provided on the museum’s online database. Determined to find out more, I went through the artist files and learned about a man named John Bennett who adopted Charleston as his home, becoming a beloved and devoted figure in the art world around the time of the Charleston Renaissance. Upon moving south, Bennett became captivated by Gullah (or Geechee) folklore and customs, which existed among communities of formerly enslaved peoples and draws heavily on West African culture and tradition. Bennett’s study of the Gullah/Geechee tradition was conducted on the streets, front porches, and backyards of his beloved town; he engaged with people and listened to their stories which drew him in with their fantastical strangeness, the kind possessed by fables of Aesop and the Brothers Grimm, as well the skillful art of the storyteller that captured the macabre beauty of these passed down tales.

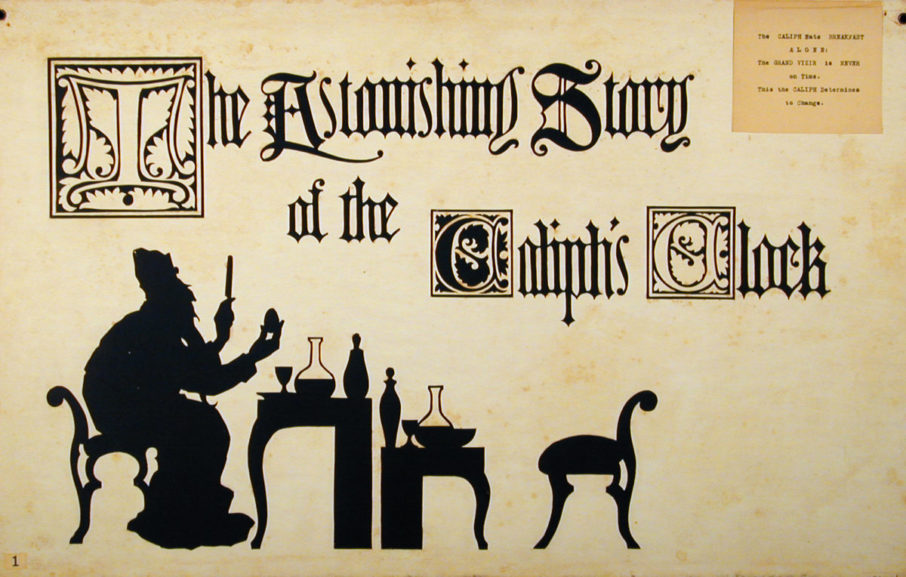

It was this strangeness of his shadow puppet-esque figures atop camels’ backs in his illustrations for The Caliph’s Clock that had captured my imagination that day in storage. This is the reason why I love art, the way it acts on the beholder and can pique this sense of curiosity when you least expect it… even when you’re, say, performing as mundane a task as inventory. In this instance, being at the Gibbes allowed me to explore the life of this artist through the letters and notes in the artist file and it was incredibly gratifying to satisfy my curiosity with firsthand accounts from the artist and his contemporaries.

The opportunities I have been afforded at the Gibbes—from working with the collection and beautiful new storage facility to pouring over archives for the upcoming Mexico and the Charleston Renaissance exhibition—have given me a much better understanding of the time and energy it takes to create each seemingly-effortless, cohesive exhibition or delicately arranged case of miniature portraits. Working at the Gibbes has made me all the more certain of my desire to pursue further education in art history and spend my life working with art, developing new and creative ways to present it to broad audiences. I hope, one day, to pay forward what I have been given working at the Gibbes by facilitating for others the kind of experience I had with John Bennett’s silhouettes that day in storage.

—Liz Feeser, UVA Summer Intern at the Gibbes, and guest blogger

Top image: The Astonishing Story of the Caliph’s Clock, Captioned: Caption: “The Central Persian Express trains were still running according to schedule; but now reached their destination an hour before they started.” Published in The Pigtail of Ah Lee Ben Loo, 1929, by John Bennett (American, 1865–1956); Silhouette, 12 x 21 1/2 inches; Gift of Gift of Susan Bennett and Mr. and Mrs. John Bennett (1957.011.0001.012)

Published July 14, 2017