This summer, I have had the incredible opportunity to intern for the Gibbes Museum of Art. I recently graduated from the University of Virginia, where I majored in Anthropology and and minored in History. Two years ago, I was at a complete loss as to what journey I wanted to embark on when I graduated. However, after internships at the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Museum and Second Street Gallery in Charlottesville, I quickly became inspired by the ways in which art from all different cultural backgrounds can beautifully represent humanity – both its diversity and inherent commonalities. I knew then that I wanted to engage with art and that my place was working for a progressive and dynamic museum, and the Gibbes Museum of Art is exactly that.

This summer I divide my time here between the curatorial and collections departments. Most people are already familiar with the role of a curator in a museum, but collections is a broad department that is just as integral to a museum’s inner-workings. Collections managers care for the physical works of art, history, literature, etc. making sure that every item is accounted for and kept in the best condition possible. I have been working with two Collections staff members: Zinnia Willits, Director of Operations and Collections, and Chris Pelletier, Chief Preparator, as we care for our objects. One of my first tasks was checking inventory for our 600-piece Miniature Collection. This required patience to dutifully record locations for every miniature and cross reference it with the location as recorded in our online database. At times, I discovered that objects had wandered from their original homes and by returning them, I was able to make it easier for future staff to locate them for research or exhibition purposes.

Another key part of collections work is condition checking, meaning to go over—in painstaking detail—every inch of a work of art and record any change that has occurred since the last condition report was conducted. I performed this task for an incoming loan of Hudson River School paintings, which had very ornate frames that needed to be carefully examined. I noted when items had been damaged while they were away from their permanent homes. Such damages are not necessarily due to any wrongdoing, but simply because they are mid-nineteenth-century gilded, fragile structures. After noting the damaged pieces, our preparator, Chris, performed repairs. I completed condition reports for all of our eighteenth-century furniture on loan in our main galleries as well.

Collections work is extremely important in running a museum; it is the basis for being able to display an important work on our walls. We would not be able to put on exhibitions without the assurance that our objects are healthy and properly documented.

Curators, on the other hand, shape content and decide the overall narratives that you see when you visit a museum. I work with Sara Arnold, Gibbes Director of Curatorial Affairs, and Amanda Breen, Curatorial Assistant, to help them research and write about objects in the Gibbes collection. Along with the Education and Digital Engagement team, we have been working on an app that will take visitors on mobile tours of the galleries, set to launch this fall. Focusing on highlights of our collection, I have been researching works by African-American artists, including Jacob Lawrence, Kara Walker, Sam Doyle, Edwin Harleston, and Mary Jackson, and writing scripts for what a visitor might see and hear as they step in front of their corresponding works. I have enjoyed this immensely and appreciate the fact that I am encouraged to engage with works in our collection created by artists with backgrounds that have historically been under-represented in the museum field.

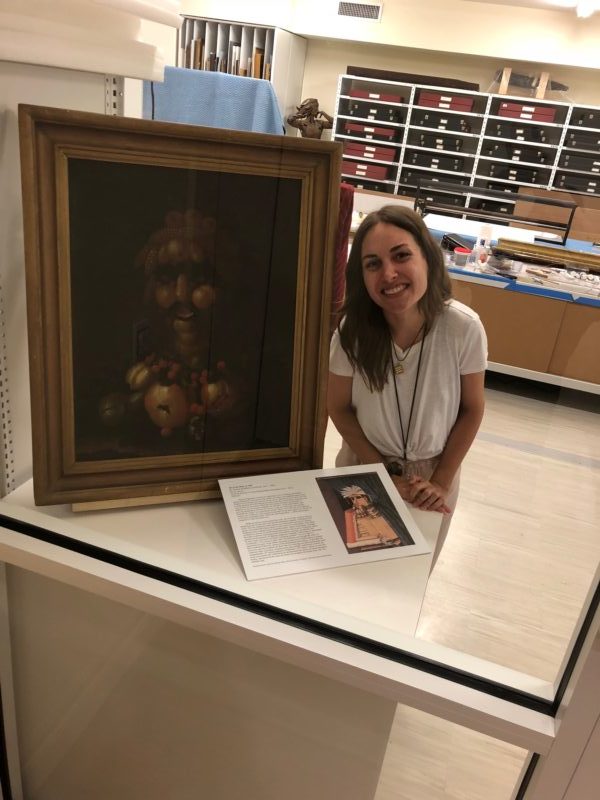

I’ve also been tasked with assignments that straddle collections and curatorial work. I was recently given the opportunity to pick any two objects in our collection for display outside of our public storage space. This is a very versatile area because it is still open to the public, but a bit removed from our regular exhibitions spaces and where our head of Collections typically highlights interesting pieces that may not be exhibited anytime soon. It’s a curatorial opportunity located in a collections space, and there is ample opportunity to get creative! This summer, I’ve spent considerable time researching pieces in our collection with unusual or important pieces that deserved highlighting.

After much scouring of our database and hunting through storage, I selected The Fruit Man by Thomas Wightman. Wightman is known for many of his realistic still lifes, one of which is on view in our permanent collection gallery. However, he was painting still lifes at a time when it was quite unpopular to do so, as most critics preferred portraiture. So, Wightman melded the two styles together in this innovative and humorous portrayal of a man made from typical still life objects — fruit! He was inspired by the late sixteenth-century Italian court painter, Guseppe Arcimboldo, famous for constructing human forms from inventive inanimate objects that often contained underlying social and political meanings. I chose to pair The Fruit Man with Arcimboldo’s The Librarian, which is printed beside the label. By comparing this sixteenth-century portrait to Wightman’s nineteenth-century version, we can look at the ways humor has continued to be incorporated into serious art forms throughout history, and marvel at the ways that our brain can recognize the human form with very minimal cues.

In completing this project, I greatly enjoyed having the freedom to research and write about something of my own choosing. I also selected a 1980 Jack Leigh photograph of Annie Mae Gadsden and Henrietta Kitty shucking oysters.

I was drawn to Leigh’s photographs in our collection because he was very adept at capturing the beauty of rural scenes and coastal lifestyles. His photographs range from quiet, unpopulated river scenes to dynamic photographs of workers amidst the steam, spray, and shells of the processing factories. I decided on this photograph because it was the only one in our collection where his subjects were named, and I felt that it was important to acknowledge the identity of these hardworking, charismatic women. In 1980, Jack Leigh felt an urgency to capture this lifestyle, feeling that the younger generations were leaving the islands in greater numbers and therefore reducing the labor population on the island. I was able to get in touch with a local expert on harvesting oysters and asked her if she thought that their lifestyle had indeed changed drastically. From this brief correspondence I learned that, at least in Beaufort county, the oyster industry is still predominantly family-owned, with some families having harvested oysters for four generations (since the 1890s!). Perhaps this way of life has not vanished as Leigh predicted, but rather the industry is more threatened by over-harvesting and high levels of pollution. Despite such threats, reflecting on Leigh’s photographs and the earnest individuals he portrayed in them can grant audiences a moment of serenity and nostalgia.

I have relished opportunities like these, in which I can incorporate my background in anthropology, and not only reflect on what art means visually, but also on the people and cultures both behind and in front of the lens, paintbrush, pencil, etc.

I am so thankful for every person who has made my time at the Gibbes so meaningful and am looking forward to implementing the skills I’ve learned in this position at my next career pit-stop.

—Hannah Hicks, Collections and Curatorial Research Intern and guest blogger

Top Image: After completing her undergraduate degree in Anthropology with a minor in History at the University of Virginia, Hannah Hicks joined the Gibbes for a summer as the Collections & Curatorial Research Intern.

Published July 27, 2018