Q & A with Rice & Ducks author Virginia Christian Beach

Q: What was the inspiration for this book?

Many people don’t know that Lowcountry South Carolina is considered a leader in land conservation in the United States. We have more land permanently protected in our coastal plain—1.2 million acres—than any other East Coast state. We are also extremely rich in wetlands and forestlands, two vital habitats for innumerable species of flora and fauna. The story of how we came to be a national model in land conservation is unique, largely due to the fact that it is predicated on the grand and tragic and complex history of the rice culture, and the convergence and interaction between northerners and southerners after the Civil War. What evolved here in the Lowcountry, what we today enjoy from a cultural and environmental standpoint, is unlike anywhere else. We felt this was an important and interesting story, worthy of a beautiful book.

Q. Rice & Ducks includes interviews with experts and scholars in the fields of rice cultivation and plantation history, African-American studies, wetland and waterfowl biology, and wildlife and habitat conservation. Tell us about your experience conducting and sifting through these interviews-the research sounds extensive!

The project took three full years, from inception to publication. I traveled up and down the rice coast of South Carolina, from the Pee Dee River down to the Savannah, with a digital recorder in one hand, pen and paper in the other, and a pair of binoculars around my neck. I sought out landowners who had been active in the land conservation movement in their respective river basins, most of whom had already permanently protected their property with conservation easements, and whose families had either been here for many generations, or had arrived with the “second northern invasion” in the 1910s, 20s and 30s.

I also interviewed slave descendants, hunting guides and land managers, as well as field biologists, foresters and ornithologists — the people living and working closest to the land. RICE & DUCKS is as much a land use history, as it is a land conservation history. One of many highlights included multiple conversations with a landowner, now in his 90s, whose great uncle had been a founding member of one of the earliest northern hunting clubs in the Lowcountry—the Okeetee Club in Jasper County—and who had wonderful memories of hunting here in the 1920s as a boy. Another highlight was walking the slave street at Friendfield Plantation in Georgetown County, where First Lady Michelle Obama’s great-great grandfather was born and raised. And lastly, walking the old rice field dikes of the Ashepoo River at dusk and watching thousands of waterfowl settling in for the night. These are just a few of the many memorable experiences of my field research.

Q. Now to the art and how “The Art Tells a Story.” Tell us how you chose the images to accompany these stories. How and why was the Gibbes’ permanent collection important to this book?

After completing my research and the manuscript, I was tasked with curating the images for RICE & DUCKS, with the help of a Curatorial Committee that included Angela Mack, Executive Director of the Gibbes, who was an invaluable guide as you might imagine. During that first year of researching the text, I also made detailed notes of artwork, maps, and visuals that I was encountering along the way, which I thought would complement and enhance the RICE & DUCKS story visually. When it came time to convene the Curatorial Committee, I created a master list of all the images I had noted, organized by chapter, and called it “A Working List of Potential Visuals.” It was over 20 pages long!

Thankfully, Angela and Steve Gavel (another member of our committee) came up with the idea of choosing a work of art for the beginning of each of the 9 chapters — giving it a full page of its own — that was representative of the overall theme of each chapter and was of the corresponding time period. This helped bring into focus and reinforce the major themes of RICE &DUCKS.

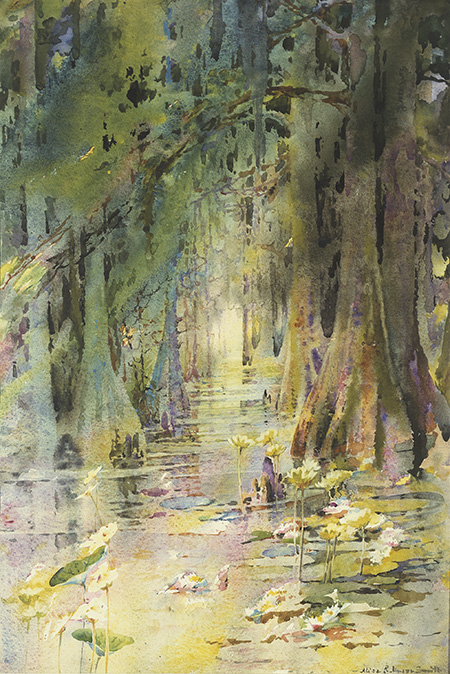

The images serve both a historical purpose and an artistic and thematic purpose. The adage that “a picture is worth a thousand words” certainly holds true for the images in RICE & DUCKS. In many instances, we simply did not have room to include sidebars and additional text on many important topics. One good example of how a painting can convey so much more information than the written word is “The Old Plantation,” lent to us by Colonial Williamsburg. With that one painting, we were able to convey much more about the history and uniqueness of the Gullah culture. Similarly, Anna Heyward Taylor’s linoleum block print from the Gibbes collection, entitled “Sowing Rice,” powerfully illustrates the African roots of rice cultivation in the Lowcountry. At the same time, Charles Fraser’s portrait miniature of Nathaniel Heyward, as well as Benjamin West’s portrait of Thomas Middleton — also from the Gibbes collection — beautifully express the aspirations and authority of the New World landed aristocracy.

Q. The proceeds from this book go toward protection of the northern breeding grounds and protection of migratory bird habitat in the Carolina Lowcountry. Can you tell us about this effort and why it is important?

You’ve heard the expression “the canary in the coal mine?” Well, migratory birds — whether they be waterfowl (e.g.ducks and geese), wading birds (e.g. egrets and herons), shorebirds or warblers— are huge barometers of the health of our overall environment, since they rely on a multitude of habitats along their ancient, amazingly long flyways. They are the great “connectors”—between continents, between nations, between habitats — breaking down political and cultural barriers as they embark on their transcontinental, cross-cultural journeys year after year after year. For example, take the little sanderlings that you see on South Carolina beaches each spring and fall. They nest in the high Arctic tundra and migrate through the Lowcountry every year, traveling thousands of miles on their annual migration between North and South America. Many of these species absolutely depend on the healthy habitat of the South Carolina Lowcountry for their survival along the way. And much of our wetlands are used by both waterfowl and wading birds and shorebirds. Saving their habitat is good for them and good for us; nourishing humankind both physically and spiritually.

—Virginia C. Beach, Author and Guest Blogger

The Art Tells the Story book signing and discussion with Virginia Christian Beach

Thursday, June 12, 12noon

$15 per person

You may pre-purchase books at the Museum Store

To purchase tickets please visit gibbesmuseum.org/events or call 843.722.2706 x21

Published June 5, 2014