I had not had the privilege of seeing a curated exhibition of Jacob Lawrence’s work in person before History, Labor, Life at the Gibbes Museum. I knew of his well-documented Migration Series (1940–41) and the famous 1972 Munich Olympic Games poster art, but was most familiar with his work through related readings and poetry. To claim to have seen work of art when only having viewed a reproduction in a book or computer screen is like saying that you’ve experienced Yo-Yo Ma’s cello playing through earbuds, streaming a compressed audio file on Spotify through your iPhone. While accessible, it’s a mere fraction of the original’s reality. Whether it’s feeling Frida Kahlo‘s acute pain and refreshing vibrancy amidst her art and life in Casa Azul, Coyoacan, or feeling oh-so-small in front of Orozco’s and Rivera’s murals the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, or getting lost in the labyrinth that is Jackson Pollock’s work at MoMA, or standing just inside the spiritual nest of Jonathan Green’s Seeking, it is bathing in this sensational range of feeling so alive that gives art its impact – a whole human experience.

Humanism is to be human, to think, to analyze, and to probe. To respond and to be stimulated by all living things—beasts, fowl, and fishes. To respond through touch, sight, smell, and sound to all things in nature—both organic and inorganic—to colors, shapes and textures—to not only look at a blade of grass but to really see a blade of grass. These things, to me, are what life and living are all about. I would call it “Humanism.”

—Jacob Lawrence

Ah, to be human. It is what Jacob Lawrence’s work captures best. The light. The shadows. The hues of black and brown that comprise the majority of our world. The shades of skin that divide and unite, yet know no borders. The blood red that runs through all of our veins. The green of the leaves on the whispering trees, the ones bearing that strange fruit. The midnight blue that peaks at the witching hour. The time Monk depicts in sound, Lawrence mixes in color. The wailing white of Mother Mahalia. The deep blue-black of Bessie’s moan. The golden glow of a lone shining star and the graying eyes of those who are moving on. A thoughtful gaze at “Forward Together,” that’s what will hold you in awe. Humanism.

The texture of survival. The wood’s grain, the flesh of grass, the scales of fish, the rippled water and curling waves. The embellished limbs, both human and terra firma. The desperation of sunken faces and bulging eyes. The joy of simple pleasures, basic rights, decent work, and dancing. The dividing lines of race and rice, dialect and cotton, gender and liquor, religion and land. Love, sex, sport. Yours, mine, ours. Humanism.

Bold. And these are just the prints. They come alive and dance right off the paper, just as sweet as I imagine Sammy swung at The Savoy.

I see Langston’s “Weary Blues,” Strayhorn’s “Lush Life,” and Billie just trying to be blessed by makin’ her own. Lawrence gave a face to Ellison’s “Invisible Man.” He gave dignity to Waller’s “Black and Blue” lyric—I can hear Satchmo crooning, “my only sin is in my skin.”

And when I stand in the presence of Lawrence’s hopeful “Brotherhood for Peace,” I see the year. 1967. Alas, the 1935 bittersweet dreams of Langston Hughes (1902–67) in “Let America Be America Again” ring true.

Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

Let it be the pioneer on the plain

Seeking a home where he himself is free.(America never was America to me.)

Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed—

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme

That any man be crushed by one above.(It never was America to me.) (1–10)

And eighty years later, my dream for the Sisterhood, too.

Humanism. His story. Her story. Our story. It’s all in his work. Jacob Lawrence did the work of bearing witness over a lifetime that spanned so many milestones of our national identity—the Great Migration, the Great Depression, the Jazz Age, the Harlem Renaissance, and beyond. He left a documented history of a people and preserved a legacy of the movement of culture in time, place, and purpose.

Lawrence said, “I hope that when my life ends, I would have added a little beauty, perception, and quality for those who follow.”

We have much to learn from those who have marched before us. They’re usually the ones with dirt on their faces. Jacob Lawrence was one such pioneer, though one would have more likely seen paint smudges in place of the dirt. As an artist, it is inspiring to humbly trace his history, labor, and life. I can only hope that the music curated for my upcoming performance of The Visual Blues of Jacob Lawrence at the Gibbes adds to the beauty, perception, and quality he left for those who follow.

—Leah Suárez, musician

On Wednesday, April 19, Leah Suárez & Friends will perform a specially-curated performance of Blues and Jazz standards inspired by the works of Jacob Lawrence on view in History, Labor, Life. Purchase tickets online here.

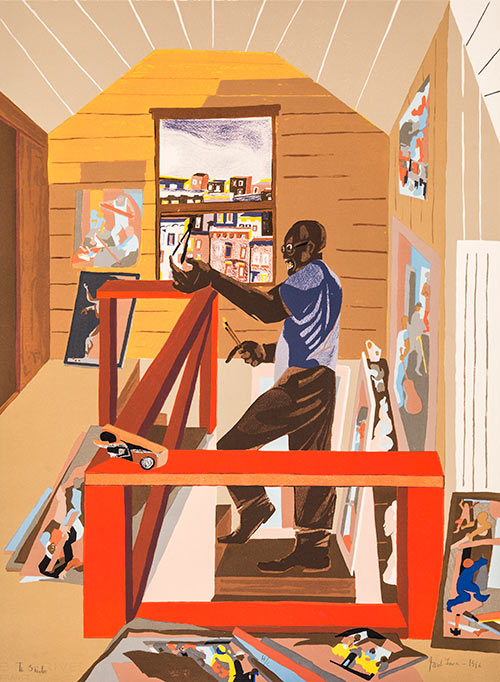

Top image: Forward Together, 1997, by Jacob Lawrence; silkscreen on paper; 25.5 x 40.125 inches; Courtesy of The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Published April 7, 2017