The artworks featured in Perspectives on Place (on view in Gallery 3 until September 10th) illuminate the history and some of the changes that have taken place in the neighborhoods on the east side of the Charleston peninsula through the eyes of Edward Hopper, Andrée Ruellan, and several other artists who, between 1929 and 1941, were drawn to depict the same city block of Charleston. The principal subject in nearly every painting and photograph featured in Perspectives on Place is a dilapidated, three-story single house fronted by a vacant lot. Identifying the exact location of this house, and uncovering all of the artists whose attention it captured is a process that has unfolded over nearly a decade.

The detective work began in 2006 when the Gibbes then chief curator and now executive director, Angela Mack, organized an exhibition featuring the fifteen paintings and drawings executed by Edward Hopper during his three-week visit to Charleston in 1929. This landmark exhibition featured paintings from the Whitney, Museum of Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and private collections. Although Hopper titled some of his paintings and left notes on others, the exact locations were not always clear so Mack set out to find addresses for the buildings that had inspired Hopper’s Charleston images. By scouring historic maps and photographs, driving the streets of Charleston hunting for clues, and tapping the knowledge of local historians, several successful identifications were made.

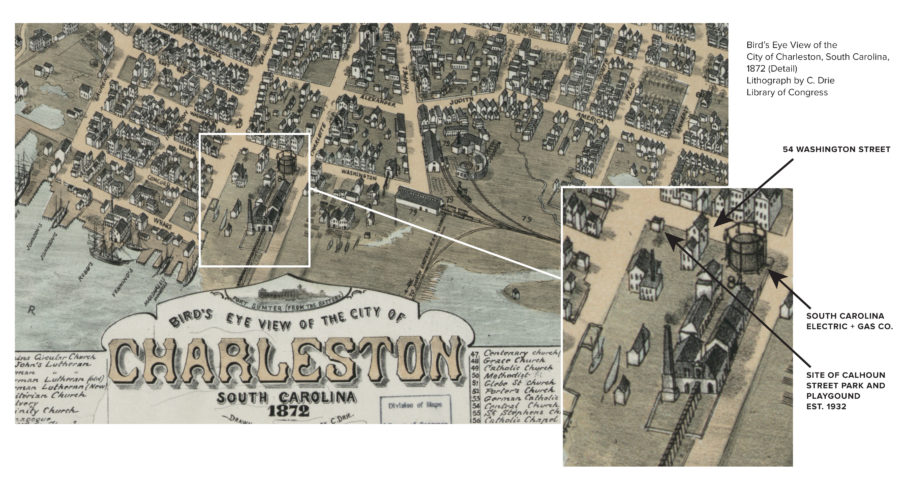

One of those discoveries was the identification of the three-story single house depicted in Hopper’s painting titled Charleston Slum as 56 Washington Street on the northeast side of the Charleston peninsula. A 1933 photograph, taken by artist Prentiss Taylor from nearly the same vantage point illustrated in Hopper’s painting, was a key to identifying the location. Housed in the Gibbes archives, and labeled on the back by the artist “Mazyckborough” the photograph revealed a large gas storage tank not depicted in Hopper’s painting that allowed us to hone in on the block at Washington and Calhoun Streets where the South Carolina Electric and Gas Company was located. Hopper chose to ignore the imposing natural gas storage tank and other industrial landmarks that surrounded the house so as not to detract from his central architectural subject.

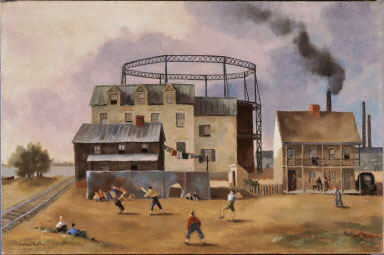

Building on the Hopper exhibition, we have since identified several other images of this same block including a study (private collection) and a painting (The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.) titled The Wind-Up by Andree Ruellan. Ruellan arrived in Charleston in spring of 1936, seven years after Edward Hopper. The two artists were friendly acquaintances. Ruellan worked as an assistant to Rockwell Kent from 1927 until 1929, and Kent occupied a New York City studio next door to his longtime friend Hopper. Until recently the setting that inspired The Wind-Up has been unknown or misattributed to Savannah, Georgia. Undoubtedly Charleston’s Mazyckborough neighborhood informed Ruellan’s composition. The paintings and photographs displayed together for the first time in this focused exhibition shed light on the history of this area and highlight how different artists impose an aesthetic vision upon the scene.

—Sara Arnold, curator of collections, Gibbes Museum of Art

August 4, 2017

Top image: Charleston Slum (54, 56, and 61 Washington Street), 1929, by Edward Hopper (American, 1882–1967); Watercolor on paper; 16×24 inches; Private collection