In a matter of days the Gibbes will open the highly-anticipated exhibition Photography and the American Civil War. The show is traveling from The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where it attracted great attendance and received rave reviews from numerous media outlets. We are thrilled to bring the exhibition to Charleston, the very city where the Civil War began with the first shots fired over Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861.

Photography and the American Civil War includes over 200 photographs, ranging from large-format, framed prints to ambrotypes and tintypes housed in handheld cases. There are also small card-mounted photographs known as cartes de visite, hand-tooled leather albums, and even Mathew B. Brady’s camera and tripod. Together, these objects explore the role of photography during a defining period in American history, the Civil War years of 1861–1865.

![Unknown photographer, [Captain Charles A. and Sergeant John M. Hawkins, Company E, "Tom Cobb Infantry," Thirty-eighth Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry], 1861–62; Quarter-plate ambrotype with applied color; David Wynn Vaughan Collection.](https://www.gibbesmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Capt-Charles_and-Sgt_John-Hawkins_CompanyE.jpg)

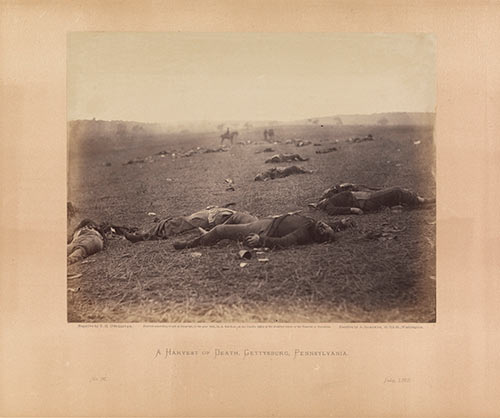

The exhibition also includes a number of battlefield views, including a well-known photograph titled A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Due to the technical complexity of producing photographs at the time, photographers rarely attempted action shots on the battlefield. They generally arrived after the battle to capture the destruction left behind. Here, Timothy O’Sullivan documented dead bodies awaiting burial on the fields of Gettysburg, a gruesome reminder of the horrors of war. Photographs such as this one were used to communicate news from the battlefield back to the homefront. In many ways, Civil War photography represents the birth of photojournalism.

A Harvest of Death also brings to mind a rather eloquent quote from a solider who fought in the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, the single bloodiest day in the history of the United States. In the words of Union Captain John Taggert: “No tongue can tell, no mind conceive, no pen portray the horrible sights I witnessed this morning.” Though no media could fully communicate the horrors of war, photography was a powerful tool for delivering information to the public and a means for loved ones to feel connected with soldiers in the field. To learn more about these and the many other roles of the camera during the Civil War, please visit Photography and the American Civil War at the Gibbes from September 27 to January 5, 2014.

—Pam Wall, curator of exhibitions, Gibbes Museum of Art

Access our mobile website, http://bit.ly/CivilWar_Photography, to learn more about the exhibition.

Information about related programming can be found on our Calendar of Programs & Events.

Published September 25, 2013