The passage of time, layers of grime, discoloration, and improper restoration efforts can all hide the true grandeur of an artist’s original work. When this happens, art museums and private collectors alike turn to professional conservators to return a painting to its original glory. The conservation process not only restores a painting to a displayable condition, but when done properly, it also provides clues to an artist’s individual techniques.

At last week’s Insider Art Series event, Colonial Williamsburg Paintings Conservator, Shelley Svoboda, shared her recent experiences in the conservation of paintings by eighteenth century Charleston artist Jeremiah Theus (1716-1774). Among the earliest artists painting in Colonial America, Theus, a native of Switzerland, arrived in Charleston in 1735 as a fully trained painter. He is best known for his portrait paintings and seems to have enjoyed a good deal of success painting Charlestonians in his vibrant Baroque style. Svoboda’s talk inspired new appreciation for this early American artist and encouraged audience members to look closely at the physical aspects of a painting from the canvas and stretcher frame to the artist’s distinct brushwork, impasto, and layering of paint colors.

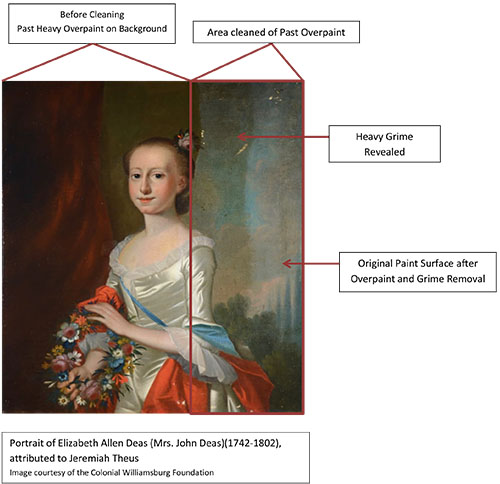

Highlighting examples from Colonial Williamsburg and the Gibbes permanent collections, Svoboda discussed challenges conservationists face when working with centuries old paintings and demonstrated the techniques used to uncover the artist’s true hand. For example, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s 2012 acquisition of the painting, Portrait of Elizabeth Allen Deas by Jeremiah Theus, added to that institution’s existing portraits by the artist creating a small, yet informative set of works representative of the artist’s oeuvre. However, major treatment was required on the new acquisition, involving careful removal of overpaint from the entire background to once again reveal the artist’s long-lost original.

In the conservation lab Svoboda used ultraviolet light to discern areas of heavy overpaint, and infrared photography and a surgical microscope to see the artist’s working technique. Once the overpaint was removed a layer of heavy grime was revealed, and preserved beneath the grime was the original painted surface ready to be revealed.

Portrait of Elizabeth Allen Deas (Mrs. John Deas), 1759, attributed to Jeremiah Theus

The Gibbes is one of the largest repositories of Theus’s work with twenty-two paintings by the artist in its holdings. During her visit Svoboda had the opportunity to review four of the Gibbes Theus paintings including the companion portraits of Charlestonians William and Mary Mazyck painted by Theus in the 1770s.

These paintings were moved to Canada by family descendants after the Civil War and were returned to Charleston in the 1980s as a gift to the Gibbes collection. Never before exhibited, Svoboda considers these paintings true treasures as they remarkably retain much of their original paint surfaces. Both are in need of cleaning and stabilization to remove the dirt, grime, and other signs of age that have drained the works of their original vibrancy. With professional conservation these paintings, like that of Elizabeth Allen Deas, could be returned to their original glory.

This spring the Gibbes will launch an Adopt a Painting program in order to raise funds for the conservation of paintings that will be featured in the new installation of the permanent collection. Stay tuned for more exciting conservation news!

—Sara Arnold, Curator of Collections

Image credits:

Portrait of Elizabeth Allen Deas (Mrs. John Deas), 1759, attributed to Jeremiah Theus

Images courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Published January 26, 2015